|

The Earth Systems Ecology Lab (www.hurteaulab.org) at the University of New Mexico is recruiting a postdoctoral researcher with a strong background in ecosystem modeling or spatial data analysis to contribute to a project aimed at understanding the interaction of climate change and disturbance impacts on western US forest ecosystems.

The initial appointment is for one year (beginning summer/fall 2023), with the possibility of extension. Salary is $60,000-63,000 per year, plus benefits. Required qualifications include a PhD in ecology, ecosystem science, earth/environmental sciences, or statistics and programming experience with R. Also, given the current backlog for obtaining a visa, applicants are required to be eligible to work in the US. Preferred qualifications include programming in C+ or C# and willingness to occasionally participate in field sampling. Applicants should submit a cover letter detailing research interests and goals, a complete CV, and names and contact information for three references to Matthew Hurteau ([email protected]). Review of applications will begin on 7 JULY 2023. The University of New Mexico is committed to hiring and retaining a diverse workforce. We are an Equal Opportunity Employer, making decisions without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, age, veteran status, disability, or any other protected class.

0 Comments

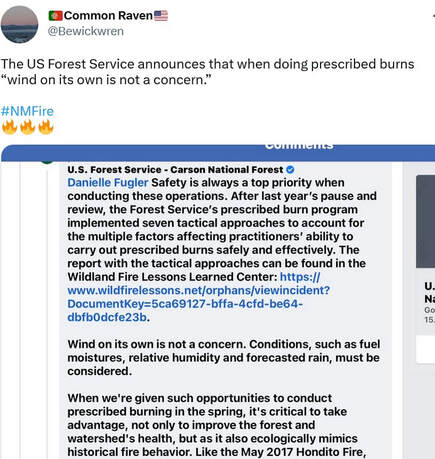

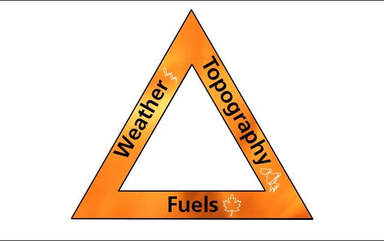

There has been much consternation over a statement from the Carson National Forest about wind on its own not being a concern in the context of a prescribed fire. It was a poorly worded statement given the Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak fire from last year and the impacts it had on many communities in northern New Mexico. However, it was correct. In this post I’m going to explain why the statement is correct and then I’m going to provide some information about how there is no future where our state is not flammable. I hope this helps people understand the decision-making in prescribed burning a bit more and that managing fuels is the only tool we have for managing wildfire risk at the local level. There are a number of good sources of non-technical information available if you want to learn more. You can check the outreach page on this website, the Southwest Fire Science Consortium, and the New Mexico Forest and Watershed Restoration Institute websites. When you live in a flammable landscape, you have to be part of the solution when it comes to managing the risk to your home, your community, and your watershed. Dr. Michael Gollner, a fire researcher at UC Berkeley, responded with the fire triangle which really encapsulates why the statement about wind was correct: The relationship between weather, topography, and fuels determine if and how a fire burns when an ignition occurs. When it is hot, dry and windy, fire spreads faster than when it is only hot, only dry, or only windy. Fire spreads uphill faster than it spreads downhill or on flat ground in the absence of wind. Fuel and fuel moisture are a key ingredient of the fire triangle and determining the flammability of a given patch of ground. If there is no fuel or the fuel is discontinuous, there is no fire spread. When fire managers conduct a prescribed fire or backburn on a wildfire they are reducing or eliminating the amount of fuel available for combustion, which will slow or stop any subsequent fire spread. Fuel is the only part of the fire triangle that we can manage to reduce risks to communities and watersheds. The amount of water stored in live and dead plants and the soil is a regulating factor on the flammability of the vegetation. If you have ever tried to start a campfire with wet wood, you know that no matter how much you blow on it the fire will not start. That is why “Wind on its own is not a concern.” is a factually correct statement. When planning a prescribed fire, the prescription that the fire manager writes lays out ranges of acceptable values for things like wind speed, fuel moisture, temperature, etc. That does not mean that if all of these factors are within the ranges specified in the prescription that it is safe to burn or even possible to burn. For example, if wind is at the upper end of the prescription range, fuel moisture is at the lower end, and temperature is at the upper end, these factors are working together to make the system more flammable. But, if the opposite is true for each of those factors, it will may be hard to get the system to burn. The point is that these factors all have to be considered in the context of each other. Throw in topography (is it flat or hilly) and the weather forecast (is it forecast to be wet, dry, etc) and there are many things can influence if and how fire burns. While I can certainly see why people living in northern New Mexico would be concerned by this poorly contextualized statement about wind, I hope this explanation helps them understand why it is an accurate statement and why all of these factors need to be considered simultaneously. It is important that all of us that live in flammable landscapes educate ourselves about the role of fire in these systems and understand the risks associated with living in a flammable environment. I’ve seen people calling for putting a stop to prescribed burning. There was legislation introduced in New Mexico during this past session to ban spring burning. These are not solutions to the problems we face because our forests are already flammable and they are becoming more flammable with increasing climate change. We spend billions of dollars every year on fire suppression and we still have wildfires that burn over communities. No matter how much money we spend, we cannot prevent or stop all fires. If we go back to the fire triangle: The only leg that we have local control over is the fuels leg. Live vegetation stores tons of water and is only available to burn under the most extreme conditions and, even then, very little of the total amount of live fuel will be combusted. On the other hand, dead vegetation is available to burn every year during fire season in New Mexico. Because we have excluded fires from our forests for as much as 100 years, there is a large amount of dead vegetation in our forests. These dead fuels dry out fast, a process that is occurring earlier in the spring because of higher temperatures and winter snow drought. The only economically viable and ecologically appropriate way to deal with these dead fuels is with prescribed fire or managing wildfires when weather conditions allow. At the same time, high temperatures and persistent drought is killing more trees and adding to this fuel, which means that fire managers are having to manage a transition to landscapes that can support fewer trees because of changing climate. Again, the only viable tool to manage this transition at the landscape scale is fire.

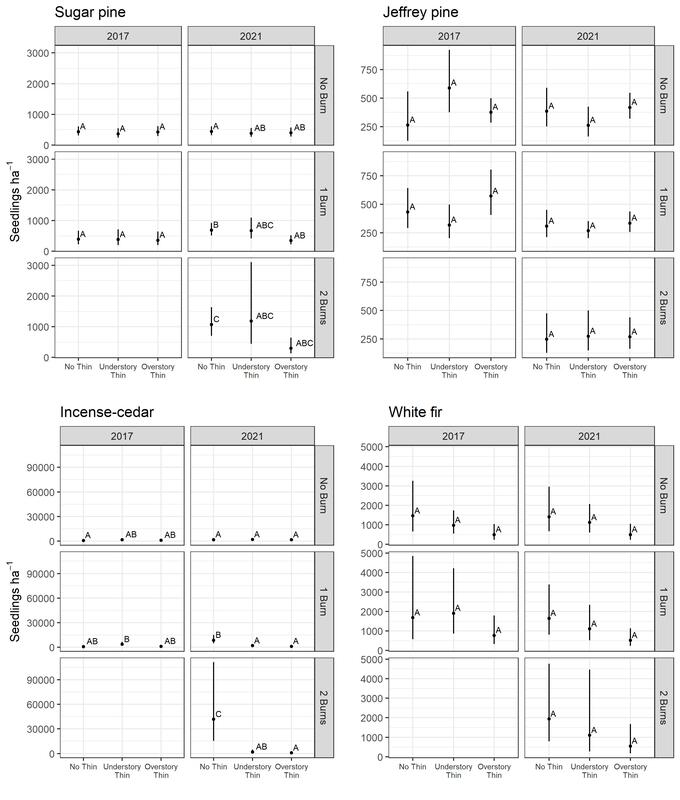

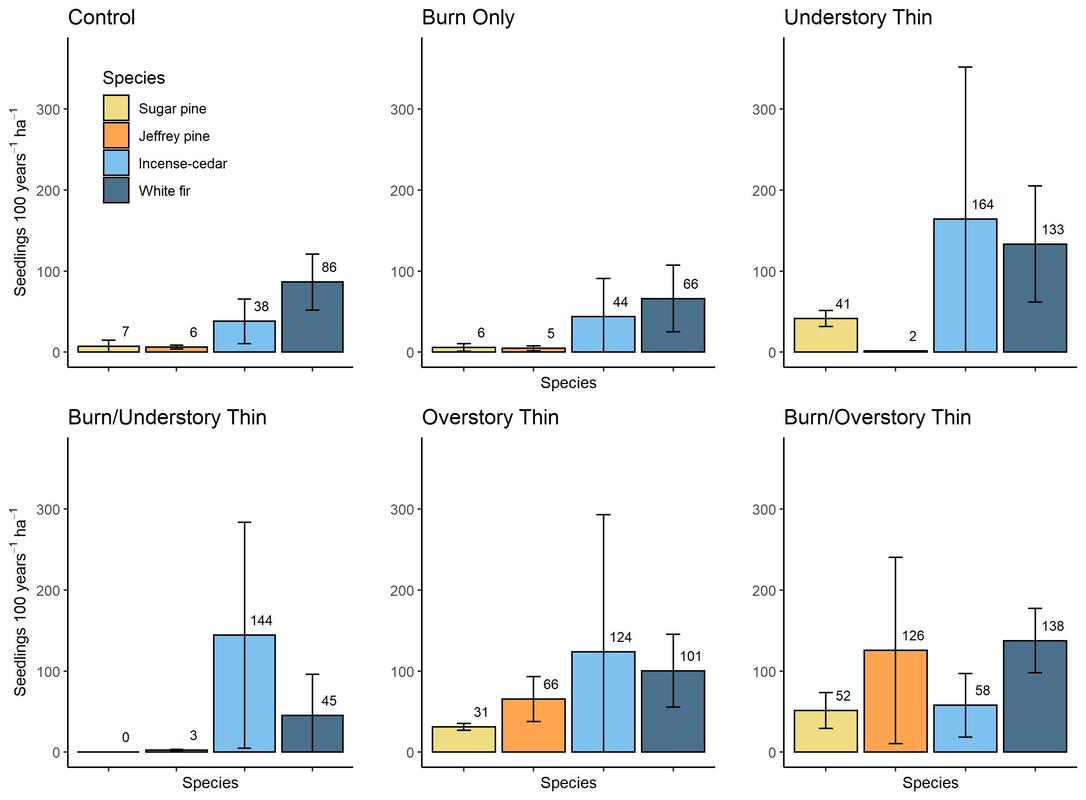

I completely understand that people are concerned about prescribed fire and the USFS doesn’t help the situation when they communicate ineffectively. But, that doesn’t change the fact that our landscapes are primed to burn because of a warming and drying climate and, because we have excluded fire for so long, they are primed to burn hot. Prescribed burning and managing lightening strikes when the weather is benign are certainly not without risk. We’ve learned that twice in northern New Mexico in the past 21 years. However, it is important not to overstate the risks of escaped prescribed fires and understate the risk that wildfires pose to our communities and ecosystems. by carolina mayOver a century of fire suppression has changed the structure and composition of forests across the western U.S. Increased tree density and a build-up of surface fuels, along with compositional changes in some forests have changed the fire regimes in low- and mid-elevation forests that used to burn regularly with surface fire to infrequent fire with a greater chance of stand-replacing fire. In the Sierra Nevada, mixed-conifer forests that were previously dominated by fire-resistant, shade-intolerant pines, now are dominated by shade-tolerant, less fire-resistant firs and incense-cedar. In light of these changes, managers implement thinning treatments and prescribed burns with a variety of management goals: reducing risk of high-severity wildfire, increasing resilience to drought and disease, and restoring historic species compositions. In our study, we assessed mixed-conifer regeneration following repeated burns in combination with thinning treatments at the Teakettle Experimental Forest. Thinning treatments were completed in 2000-2001 and included an understory thin, which removed small diameter trees, and an overstory thin, which removed larger diameter trees. Prescribed fires were completed in 2001 and 2017. Six total treatment combinations were evaluated, including an untreated control. Following thinning and burning, overstory-thinned plots were planted with Jeffrey pine, sugar pine, and white fir proportional to their original overstory tree dominance. Our analysis focused on the regeneration of the four most common species across the experimental area: Jeffrey pine, sugar pine, incense-cedar, and white fir. We estimated seedling densities for each species on plots that had experienced no burns, one burn, or two burns, in addition to initial thinning treatments. We found that repeated burns led to modest increases in sugar pine regeneration and substantial increases in incense-cedar regeneration, with no significant effects detected for Jeffrey pine or white fir. Estimated seedling densities are shown in the figure below, with letters indicating when treatments are different from one another during a given year.  Estimated mean seedling density by species for each burn and thinning treatment combination from 2017 (pre-second burn) and 2021 (four years post-second burn). The letters are for comparison between treatments within a given year. Different letters mean that two treatments are statistically different. We also estimated recruitment of seedlings to the midstory over a 16-year period, by calculating how many seedlings grew to exceed 5 cm in diameter for each treatment combination. We scaled this rate over 100 years to provide an estimate of long-term recruitment rates, shown in the figure below.  Species-specific rates of midstory recruitment per hectare scaled over 100 years. Mean recruitment rates are calculated from records of new trees tagged and mapped plot-wide at each measurement period from 2002-2003 to 2018- 2019. Overstory Thin and Burn/Overstory Thin plots include recruitment from both planted seedlings and natural seedlings. Estimated recruitment rates were much higher for incense-cedar and white fir than for the two pine species, which remained low even following burning and understory thinning treatments. Historically, this forest supported around 18 mature sugar pine, 15 Jeffrey pine, 10 incense-cedar, and 23 white fir per hectare. At our current estimated rates of pine recruitment for unplanted treatments, it would be unlikely to impossible to achieve these pine densities. However, overstory thinned plots that were planted post-thinning had much higher pine regeneration rates. In fact, the majority of pines recruited to the midstory on overstory thinned plots were originally planted.

Our results indicate that repeated prescribed burns, even when combined with thinning treatments, may fail to achieve pine regeneration at a rate sufficient to restore a pine-dominated overstory. Regeneration of shade-tolerant white fir and incense-cedar remains high, and additional thinning of these species may be necessary to reduce seed production. Although uncommon after forest thinning and burning treatments, planting pine may be an effective tool for managers to increase otherwise low pine recruitment in these forests. |

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed