|

The process for applying and being accepted to a graduate program varies by discipline. In some disciplines it is similar to applying for admission to university as an undergraduate, you are applying to the program and will identify an advisor during your first year. In ecology you typically need to have identified an advisor before you are accepted. I’ve worked at two different universities and been a faculty member of three different graduate programs and, in all three programs, to accept a student I had to put together a funding package. As a result, you could be the best applicant our program has ever seen and if no one is willing to accept you into their lab, we will not admit you. Below I’ll highlight the process I use to identify graduate students and the advice I give all potential graduate students that I interview.

My approach: Gaining admission in my lab starts far in advance of the actual application process. I have a potential students page on my website and it states the information that I want students to send me (CV, 1-page statement of research interests, unofficial transcript). If a student doesn’t include those things, I know they haven’t looked at my website in detail and assume they are not real serious about joining my lab. Our program application deadline is usually right after the new year, but it is best if students contact me in late-summer. If I don’t have funding or am at capacity for number of students in my lab, I let potential students know right away. In my department, we have teaching assistantships (TA) available for the academic year that provide a stipend, tuition, and health insurance. However, that is only part of a funding package. Before I take a student I make sure I have at least the first couple of years of summer support for them, money to buy a new computer, and enough discretionary money to support the research project they choose to pursue for their thesis. Assuming the student will TA, I still need to have about $20,000 on hand to support their first two years. However, I like to have my students both RA and TA each academic year, which means I need another $20,000 per year to support a semester of RA. The other consideration is – do I have the time to support another student? This depends on the number of students in my lab and their stages, the number of postdocs in my lab and their stages, and the amount of commitment I have made to various projects. If I don’t think I can provide adequate time to support a new student, I let them know. I take this seriously. If a student has been awarded a fellowship and won’t require any financial commitment, I still agree to advise them if I don’t think I can give them proper support. If I’m looking to have a new student join my lab, my informal application process starts with students sending me their materials. Then I set up video calls with each applicant and discuss their research interests, current projects, my expectations, and my approach to mentoring. I tell them to contact my current lab members to get their take on my approach. After I conduct interviews, I reach out to the student that I would like accept into my lab and recommend they formally apply to the program. I use this process because I don’t want students paying to apply to our program and the admissions committee investing time in reviewing their application if I have no intention of agreeing to serve as their advisor. Finding the right advisor: Assuming you’re totally stoked about a particular discipline and have determined that graduate school is the next right step, the daunting part of finding the right advisor begins. As you are reading the literature in your chosen discipline, pay attention to the authors. Is there a particular set of research that has a common author that you find intriguing? If so, look them up and read some of their most recent papers. If you are still interested in what they are doing, look at their website and see if they have a process for potential students. If not, send them an email introducing yourself and state your research interests. Make sure to attach your CV. If you don’t hear back, do not take that as a reflection of their opinion about your qualifications! We are all busy and sometimes emails slip by. We are all people and sometimes we have personal things happening that cause us to triage work/emails. And, some of us are just plain bad at responding to email. Assuming you do get a positive response, there are some things that you want to find out. Remember, you are interviewing the potential advisor as much as they are interviewing you. Here are a several that I recommend:

Use this information to help determine if this person may be the right advisor for you. Assuming you get a positive response from the potential advisor and you apply, it is important to make an in-person visit. In our program, we organize a recruiting weekend. Each potential advisor pays for the plane ticket, the recruit spends two nights staying with a current graduate student, there is an on-campus program to meet faculty and students, and then there is a field trip and night at the field station. If the program doesn’t have a formal recruiting event like this, find out if you can visit anyway. This is an important decision and you need to do your homework to make sure, to the best of your ability, that you make the right decision. Additional notes: When I am interviewing students before encouraging one to apply, there are always some that I don’t encourage to apply. If you end up in that situation, it is not a reflection of whether you will do well in graduate school. Sometimes I don’t encourage students to apply because their research interests are not close enough to my expertise that I will be able to advise them. As an example, if a student tells me they’re interested in forest structure and bird habitat, I’m not the right advisor even though I study forests. I don’t know anything about birds. It is up to you as the student to determine if a particular advisor and their lab are a good fit for you. Your potential advisor cannot make that assessment for you, all they can do is honestly tell you how they approach mentoring students. Make sure you talk to current and former students to triangulate on the potential advisor’s mentoring approach. Some advisors are great for some students and bad for others. It really depends on the advisor’s approach and the student’s needs. When you first email a potential advisor, formality is best. Dear Dr. X or Professor X is the best way to start. Some of us grew up in a time when we still wrote letters on paper and sent them via snail mail and “Hi,” doesn’t cut it. Final thoughts: You don’t have to go straight to graduate school from your undergrad. If you are unsure about your desire to pursue an advanced degree or unsure about the specific discipline, go spend some time working in that field after your undergrad and figure it out. You are young and there is plenty of time to make sure you make the right decision for you. Don’t be intimidated to reach out to a potential advisor. One of the things that my colleagues and I often hold up as one of our favorite parts of our jobs is advising students. The other thing I will reiterate is that there is a lot of rejection in science. Do not take rejection in this process as a sign that you are incapable, unqualified, or any of those other places the mind can go when rejection happens. Many of us in science didn’t follow a straight line to get to where we are, me included.

0 Comments

Assuming you’ve thought long and hard about why you want and advanced degree in ecology and what specific sub-discipline you’ve decided to pursue, below I provide some advice on how best to approach the grad school application process.

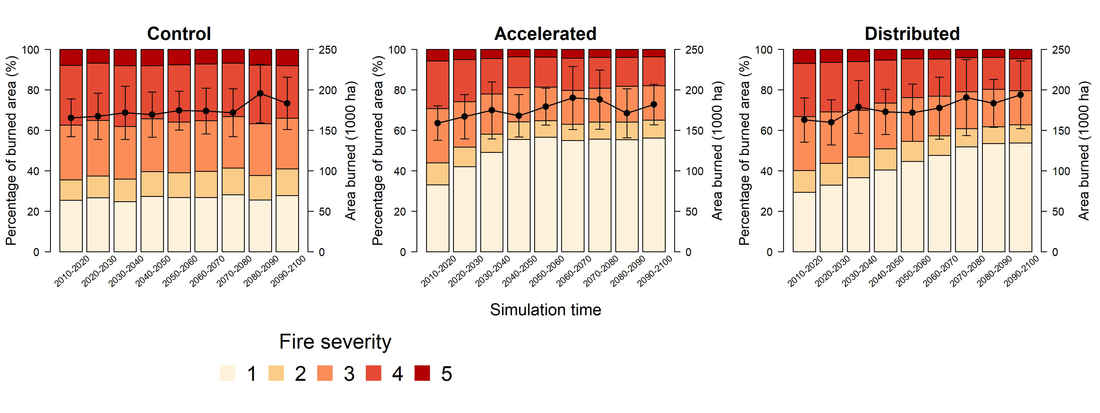

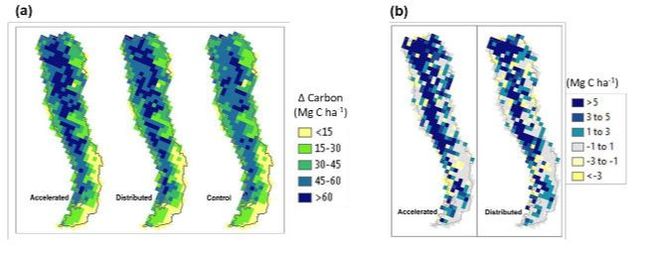

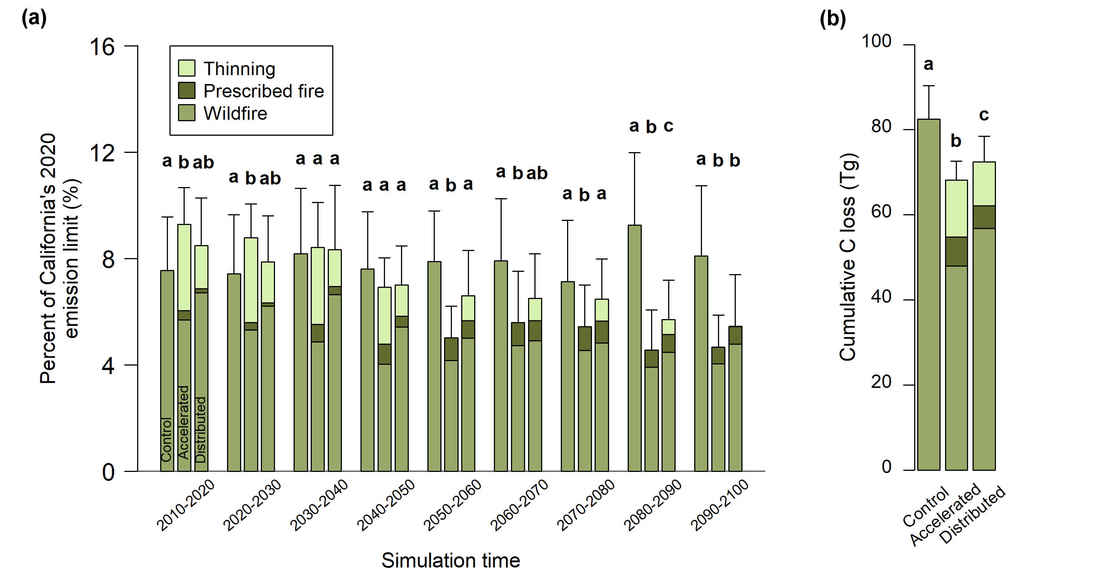

Do not just apply to a program without first contacting potential advisors. Every year I get 1-3 students that do this and list me as their potential advisor. If I’m taking students that year, I’ve already encouraged 2-3 students to apply and will not look at your application. You may think that is harsh, but here is why I do what I do: I don’t want students to spend the time and money required to apply to our program unless I think they will be a good fit in my lab and that I think I will be a good advisor for them. Here is what you should do. Reach out to people whose work interests you 2-4 months before the application deadline. Hopefully you’ve identified these people based on their publications. Make sure that you check their website for materials that they request of potential applicants and provide them with your initial email. I ask for a CV, a one-page description of research interests, and unofficial transcripts. I’m not looking for a ground-breaking question that you want to pursue. I’m trying to evaluate if you’ve thought through what you want to research and if you can present it in a coherent manner. Assuming you get some interest from the potential advisor, then you need to plan for your first interaction with them beyond email. I schedule a video call with potential students so that we can each learn more about how the other operates. You need to be prepared for questions relevant to the work we do in my lab. I often ask potential students which of my papers they found most interesting and why? Your answer will help me understand why you’re interested in the work we do and what specifically about forest ecology gets you excited. After having interviewed several students, I’ll recommend that 2-3 formally apply to our program. Sometime following your application, it is important to schedule a visit. Many programs/advisors will support your travel to visit, but even if they don’t, this is a worthy investment. This is your opportunity to get a sense of the department and the program. Most importantly, this is your opportunity to meet with your potential advisor and lab. I schedule time for potential students to meet with my current lab without me present. You need to ask current students how your potential advisor operates, what kind of support they provide, and what their expectations are. This is your opportunity to gather data about how well you think the potential advisor’s approach will work for you. You should also feel free to contact students who have graduated from the lab. They have a complete picture of the process. To make this process effective, you need the self-awareness to know what you require to be successful. Make sure you give this some thought well in advance of this process. Remember, this process is a two-way street. The potential advisor is interviewing you, but you also need to be interviewing them. The area burned by wildfire in the Sierra Nevada has increased by 274% over the last 40 years and the area impacted by stand-replacing fire has also increased. The forests in the Sierra Nevada are important for provision of clean water and are also part of the state’s climate action plan. As a result, figuring out how to reduce the chances of large, hot fires presents a large challenge. We know that the current pace and scale of forest treatments to reduce the risk of large, hot fires is inadequate given the scale of the problem and the area burned by wildfire is projected to increase with on-going climate change. In a recent study led by Shuang Liang, we set out to determine how the pace of large-scale treatment implementation would alter carbon storage across the Sierra Nevada. We ran simulations under projected climate and wildfire and two management scenarios. Both management scenarios included applying thinning and prescribed burning treatments to low and mid-elevation forests. These are forests that have been most impacted by fire suppression. In the distributed scenario, we simulated an equal portion of the area treated at each time-step and with full treatment implementation by the end of this century. In the accelerated scenario, we simulated the same treatments over the same area, but schedule the treatments so they were complete by 2050. We included a control scenario that assumed no active management for comparison. The area burned between all three scenarios was fairly consistent because we used the same fire size distributions in our simulations (black line in Figure 1). However, the proportion of burned area that was burned by stand-replacing fire (severity 4 and 5) decreased substantially. The faster pace of treatment under the accelerated scenario increased the proportion of area burned by surface fire (severity 1 and 2) and decreased the area burned by stand-replacing fire at a much faster rate than the distributed scenario. Both the accelerated and distributed treatments ended up storing more carbon than the control by 2100 (Shown by the difference in Figure 2). However, what was most striking was how these treatments influence the carbon balance of Sierra Nevada forests as a percentage of California’s 2020 emissions limit from the Governor’s Climate Action Plan. Initially, total carbon losses are higher in the treatment scenarios, with the accelerated treatment having the largest loss (Figure 3). However by 2030, carbon loss is similar amongst all three scenarios and by 2050 the accelerated scenario has lower emissions than the wildfire emissions under the control. As we demonstrated in a previous study, changing climate and the increase in area burned has the potential to increase wildfire emissions by 19-101% by later this century. The results from this study demonstrate that restoring surface fires to the low and mid-elevation forests in the Sierra Nevada can reduce the magnitude of future emissions and maintain a larger amount of carbon stored in these forests.

|

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed