|

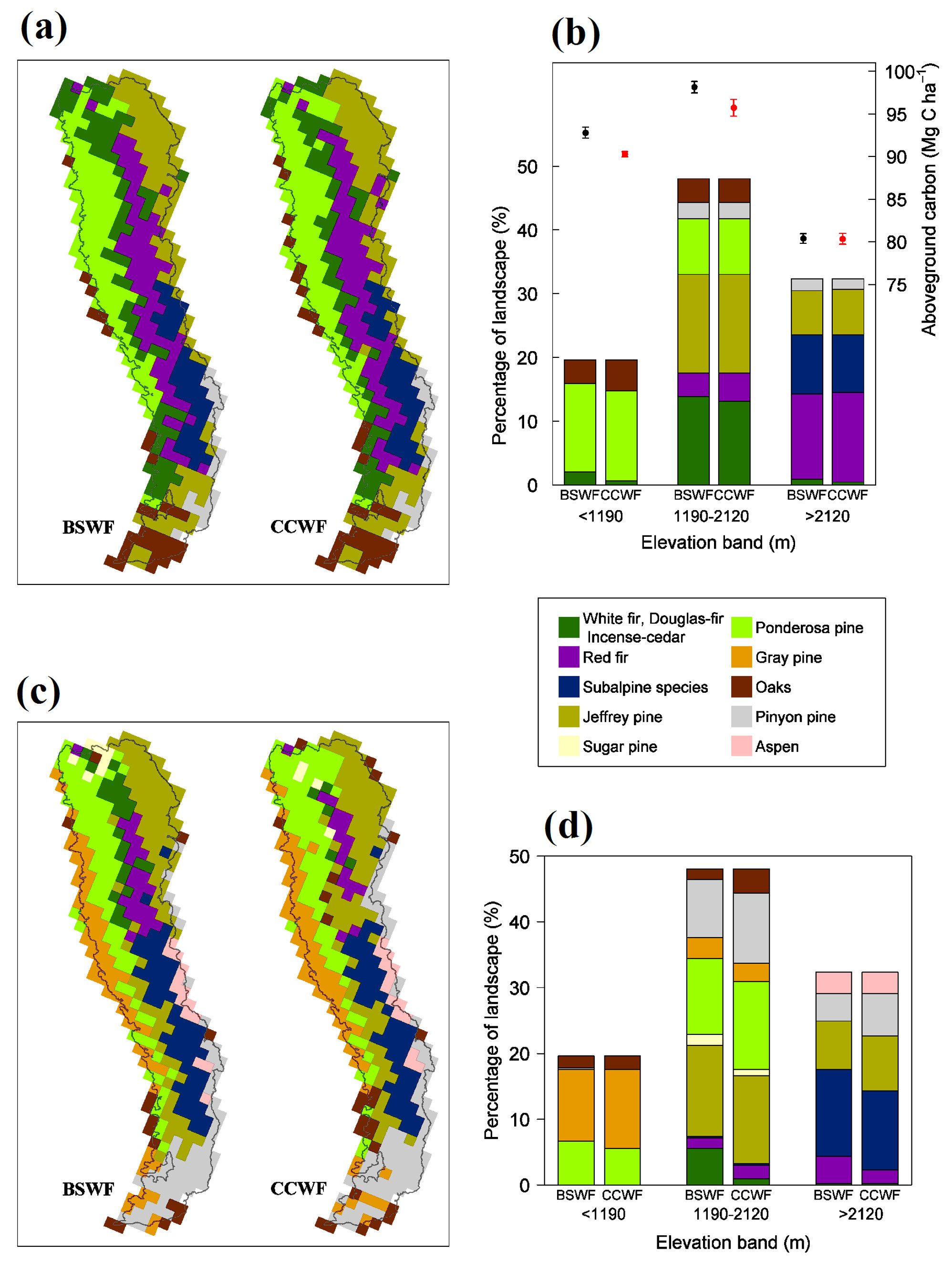

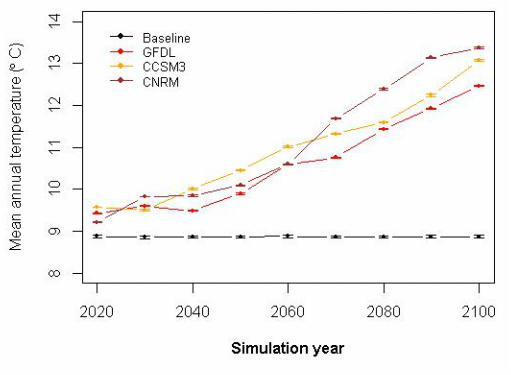

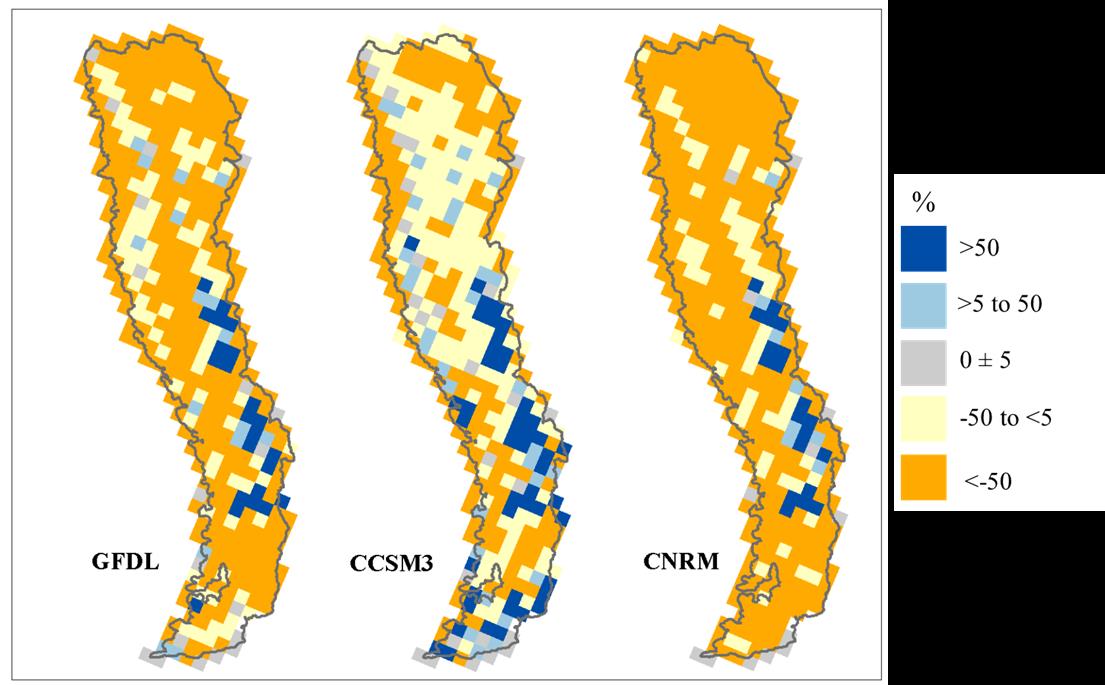

Trees can live for hundreds to thousands of years. With that kind of lifespan they certainly experience a range of climatic conditions. When we move from thinking about the tree to thinking about the forest and how changing climate might impact a forest, we’ve got to consider how climate influences tree regeneration. There is a body of research that has examined the climatic conditions under which different tree species will regenerate. The range of climatic conditions that a seedling will tolerate is generally much narrower than the range of conditions a mature tree will tolerate. In a recent study led by Shuang Liang, we examined how future climate change and wildfire might alter the distribution of tree species across the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California and Nevada. We used the LANDIS-II simulation model, projected climate data from three climate models, and area burned projections to simulate the forests of the Sierra Nevada. The climate models show that with unabated human carbon emissions we can expect about 3-5°C of warming by 2099, which will dry out the environment leaving forests with less water for growth. When we ran simulations we used the three climate projections in Figure 1 and we also ran simulations with climate from the period 1980-2010 to create the baseline scenario. This baseline case included area burned data from the same period and provides a comparison with the future climate and wildfire scenarios. When we looked at how future climate and wildfire impacted where different tree species were on the landscape, we found small changes for the mature trees (Fig 2 a,b). At the lowest elevations, we found slight declines in tree species like white fir that prefer more precipitation, but changes in the distributions of other species were quite small. However, when we looked at tree regeneration, we found large differences between the baseline scenario and the future climate scenario. In the middle elevation band (3900-6900 feet), we found sharp declines in the amount of regeneration events for the more moisture loving species like white fir and we found that more drought-tolerant species like ponderosa pine had accounted for more of the regeneration (Fig 2c,d).  Fig 2: The spatial distribution of dominant tree species by biomass (a) and by elevation band (b). The spatial distribution of dominant tree species by number of regeneration events (c) and by elevation band (d). The results use baseline climate and wildfire (BSWF) and projected climate and wildfire (CCWF). We also found sharp declines in the number of regeneration events over the 90 year simulation (Fig 3). The majority of the mountain range had 50% fewer regeneration events with future climate and wildfire than did the baseline scenario. When you’ve got forests that experience wildfire, reduced regeneration is important because it means that areas that burn will take longer to recover to forest. When we compared the percentage of the Sierra Nevada that was not forested in 2099, we found that it had increased by about 5% over the baseline climate scenario. Now, 5% doesn’t seem like much, but when you are talking about the whole Sierra Nevada mountain range that is approximately 170,000 hectares (656 square miles).

These results suggest that we can expect some pretty large changes in the species that make up the forests of the Sierra Nevada and the amount of area that has forest cover as the climate changes.

0 Comments

|

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed