|

The Earth Systems Ecology Lab (www.hurteaulab.org) at the University of New Mexico is recruiting a postdoctoral researcher with a strong background in ecosystem modeling or spatial data analysis to contribute to a project aimed at improving our ability to model smoke impacts on photovoltaic energy production in the western US. This project will include parameterizing the LANDIS-II model for a new location and running simulations to quantify the influence of changing climate and wildfire on biomass accumulation and consumption. The project will also work to refine partitioning of NPP into different fuel categories to better crosswalk output with the WRF model. The project is in collaboration with researchers at Sandia National Lab and the National Center for Atmospheric Research. The researcher will work as part of an interdisciplinary collaborative team.

The initial timeframe is a two-year project. The initial appointment is for one year (beginning summer/fall 2023), with the possibility of extension. Salary is $62,000-68,000 per year, plus benefits. Required qualifications include a PhD in ecology, ecosystem science, earth/environmental sciences, or statistics and programming experience with R. Preferred qualifications include programming in C+ or C# and willingness to occasionally participate in field sampling. The preferred start is January 2024. Applicants should submit a cover letter detailing research interests and goals, a complete CV, and names and contact information for three references in a single pdf to Matthew Hurteau ([email protected]). Review of applications will begin on 30 OCT 2023. The University of New Mexico is committed to hiring and retaining a diverse workforce. We are an Equal Opportunity Employer, making decisions without regard to race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, age, veteran status, disability, or any other protected class.

0 Comments

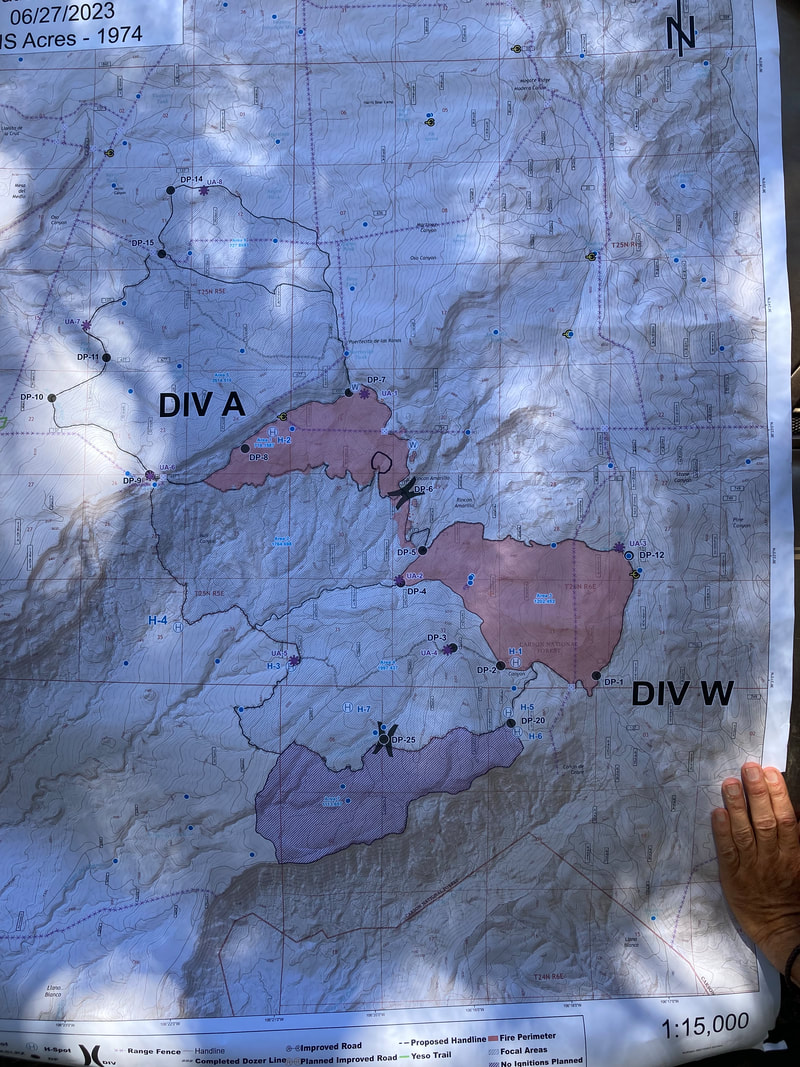

This post follows a more general post about managed fire, which you can read here. One of the best parts about my job is that I have a backstage pass to the natural world. As my friend and colleague Craig Allen likes to say, as scientists “we are interpreters for the natural world”. On 6 July I got to tour the Comanche Fire on the El Rito ranger district of the Carson National Forest with District Ranger Angie Krall and a number of staff members from the Carson. It is still an active fire, so we got briefed by the Incident Commander on operations and we got an overview of the decision-making around this ignition and their choice not to immediately suppress the fire. The people on the field tour included researchers, non-Forest Service collaborators working in the area, and a couple of members of the press. What follows is my summary of the information. Since I was typing this on my phone and my thumbs are large and I’m at the age where I need cheaters to read, anything (dates, acres, etc) that is incorrect is because I either didn’t hear it correctly or wrote it down incorrectly. These dates and numbers may be important to some, but what is important about managed fire is the decision-making process and the outcome. Those are where I focused my attention. The Comanche Fire started as a lightening ignition on 8 June. Here is a photo of the ignition site. The ignition site is in complex terrain, which is fire manager speak for rugged country (e.g. cliffs, canyons, peaks, etc) that is dangerous for firefighters. Federal fire policy allows managers to make a choice when an ignition is ‘natural’ (e.g. lightning). They can either suppress the fire or they can manage the fire for resource benefit. Keep in mind, this is not a binary decision. Sometimes managers may choose to manage for resource benefit on one side of the fire and work to suppress it on the other side. It really depends on objectives and risks. Below is an operations map that I’ll use to described the decision-making that went into the Comanche Fire. To orient you, the line around the outside of the areas marked Division A and W the red area and the purple area is the area that managers evaluated for burning. This is what fire managers call drawing the box. The first decision point has to do with firefighter and community safety. In this case, there were no communities threatened, but as I mentioned this is rough country and risks to people working the fire go WAY UP when in ‘complex terrain’. The next decision point has to do with weather and moisture in the vegetation, forest conditions, and the position relative to previous fires and management activities. The wet spring and mild weather conditions meant that fire would burn at lower intensity and be beneficial for the forest. Downwind of the ignition point are previous wildfire burn areas and prescribed fire areas with less vegetation to burn. These are places that fire crews can use to contain the fire. As a result of these factors, the managers decided they could draw a bigger box to decrease the safety hazards for fire crews. But how big is the box? Those previous prescribed fires and wildfires and the topography help determine what the fire crews have to work with for containing the fire. The managers then work with resource managers (archaeologists, wildlife biologists, and many others) to evaluate if and what could be impacted by fire. These pieces of information help them determine the size of the area (the box) that they will consider allowing fire to burn if the effects of the fire are going to be beneficial for the forest. In the case of the Comanche Fire that box is approximately 10,000 acres (the black outline). Now that the box is drawn, what comes next is the plan to manage the fire. There are two common misunderstandings about this process. The first is that fire crews sit back and wait. That would be crazy because if the weather changes or something else happens and the fire spread increases dramatically, that increases the chance it gets out of its box. To keep it in the box, they use those landscape features like ridges and road to start working with the fire by burning from these features to control how quickly the fire can spread. This is the second common misunderstanding. When fire crews light by hand or with helicopters or drones, this does not make it a prescribed fire. The same thing happens when they are suppressing a wildfire; they are trying to reduce fuel in areas they plan to use for containment. The red areas on the map are the areas that actually burned in the Comanche Fire and along the perimeter and in the interior are the places where fire crews lit fire to manage the how quickly the fire spread and the effects it had on the forest. This includes creating fire line around springs and burning from that fire line to protect the area. We hiked up a ridge line to get a landscape perspective of the fire. In this photo you can see a patch of oak that is the result of some tree torching during a prescribed burn in the early 2000s. You can also see a small patch of tree torching from the Comanche Fire. These are not ‘bad’ outcomes because they are small. These forests were much more patchy two hundred years ago and will be better able to tolerate ongoing climate change and more fire if we restore that patchiness. The other thing you should notice is how much green forest is still in that fire footprint. Managing fires and changing tactics

Later in June weather conditions began to change. Temperatures increased and that caused the vegetation to begin drying out. By itself, lower fuel moisture is not a big deal, but a wind event was forecast. By 20 June, managers decided that they because of wind and drying conditions they were not getting the beneficial fire effects that were the objective and that weather conditions were increasing the risk to fire crews and the public. At that point they called in aerial retardant drops along the southern boundary to stop the fire spread. This decision point was misinterpreted by some as the fire crews having ‘lost’ the burn. The red polygon is still well within the perimeter designated by managers as appropriate for this fire event. Nothing was lost. A change in decision was made in response to changing conditions. At the time of our briefing, total burn area was 1974 acres (red polygon) and approximately 20% of the area covered by the red polygon was unburned. These 1974 acres of forest are in better ecological condition than they would have been in the absence of the Comanche Fire. This is the type of fire we need to encourage in our southwestern forests because it is ecologically appropriate and it is an important part of decreasing the risk of high-severity wildfire to communities and watersheds. The easy decision in fire management is to suppress an ignition. No matter what happens, if fire managers tried to put it out, they are treated as heroes. The much harder decision is to choose taking advantage of conditions to achieve outcomes like that of the Comanche Fire. There are more risks, but also much better forest management outcomes. Many of our forest types in the southwestern US burned at high frequency before land-use change (e.g. heavy grazing in the mid-1800s) and fire suppression (starting in the early 1900s) excluded fire from these ecosystems. A couple of wet periods in the early 1900s and lots of tree regeneration led to the dense forest conditions we see today that are capable of sustaining stand-replacing wildfire. Research dating back to the 1970s has shown that excluding fire from these forests was a problem and we have known with lots of confidence since the 1990s that reducing tree density and the amount of dead vegetation in the forest is central to reducing the chance of these high-severity, stand-replacing wildfires. Forest managers used this research to design thinning and prescribed burning treatments to accomplish the goal of restoring fire and decreasing high-severity fire risk, but the pace and scale at which treatments were being implemented was not sufficient given the amount of forest requiring restoration. Meanwhile, forest managers on the Gila National Forest and Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks started working to manage naturally occurring fires to restore the system. They did this in the backcountry where there was less chance of the fire causing harm to humans and their objective was to do this when weather and moisture conditions would allow the fire to burn in a way that is beneficial to restoring the forest. While this was happening, many people (myself included) were advocating for more funding to land management agencies to accomplish more forest restoration. Fast forward to 2020 and Congress appropriated a significant amount of money for forest restoration. Yet, the scale of the problem means that there still is not enough money to restore all of the forest using thinning and prescribed burning. I did a back-of-the-envelope calculation after the legislation passed and estimated that if you wanted to thin and prescribed burn every acre of forest on the Santa Fe National Forest that used to burn regularly, it would cost over $1 billion. There is no way we are going to make that level of investment.

There are all kinds of other things that make thinning and burning treatments slow to implement and costly, too. The simple economics of having to pay to thin the trees because they are small diameter and wood products are cheaper to make from trees grown in productive places can mean thinning costs of $2500 per acre. Then there is the NEPA planning process and the surveys for archaeological sites and endangered species that are required before work can begin. Both take time and cost money. Meanwhile, if a lightening strike or camp fire starts a wildfire, land management agencies can mobilize tons of resources (billions of dollars per year) and suppress the fire. Big fires means bulldozers and dropping retardant from airplanes and all sorts of other things without any sort of environmental assessment. The punchline here is that the best thing we can do for the ecology of our fire-prone forests is to restore fire that helps maintain the system so we don’t need to mobilize suppression forces and fight against this process at all costs. Escape prescribed fire Restoring fire to forests is not without risk and we have to acknowledge the impacts of the Calf Canyon-Hermits Peak wildfire on the communities and ecosystems of northern New Mexico during spring 2022. My colleagues and I wrote a number of op-eds during the 2022 fire season and you can read those here: Use all the tools - including fire Use all the tools to improve forest health Prescribed burning can work Increasing the pace and scale The other tool that forest managers have is choosing a different management approach when a lightning-caused fire starts. When a so-called natural ignition happens and weather and vegetation moisture conditions are right and the risks to things of value are low, managers can do what the Gila National Forest and Yosemite and Sequoia-Kings Canyon National Parks have been doing for decades – they can manage that fire to benefit the ecosystem. Federal policy has called it many things over the years. The most recent incarnation is called managing fire for resource benefit. Much to the chagrin of the higher-ups in land management agencies, everyone else calls it managed wildfire. No one has ever accused a big bureaucracy for choosing clear terminology to describe their actions. Managed wildfire can accomplish the objectives of thinning and burning, but at a much larger scale and, typically, a much lower per acre cost. There is a huge misunderstanding in the public about managed fire and I will use the Comanche Fire, which I toured on 6 July, as a case study to explain managed fire in this post. We here in the southwest have chosen to live in and depend upon flammable landscapes. Even if you live in the city, the water that flows out of your tap is coming from a watershed that is covered in fire-prone forest. It is our responsibility to learn about fire in our landscapes and contribute to helping reduce the risks posed by our past societal choices. We need to prepare our homes and ourselves for what this means and use the resources available to prepare. A couple of resources for living in flammable landscapes: How to prepare your home How to construct an inexpensive air filter |

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed