|

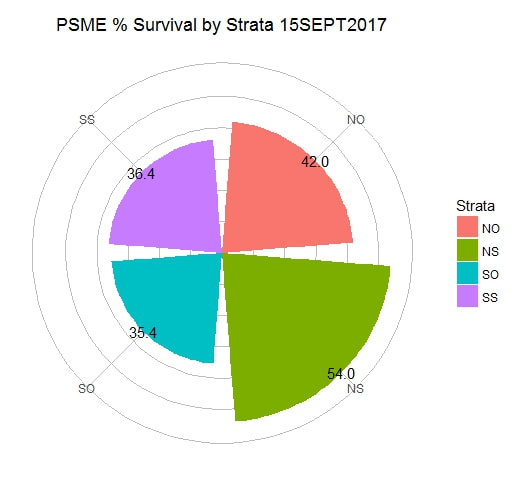

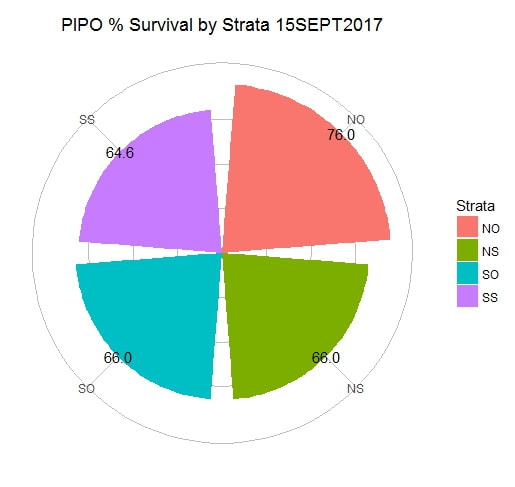

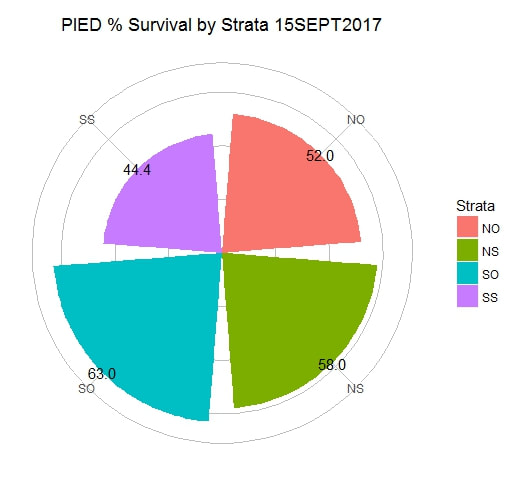

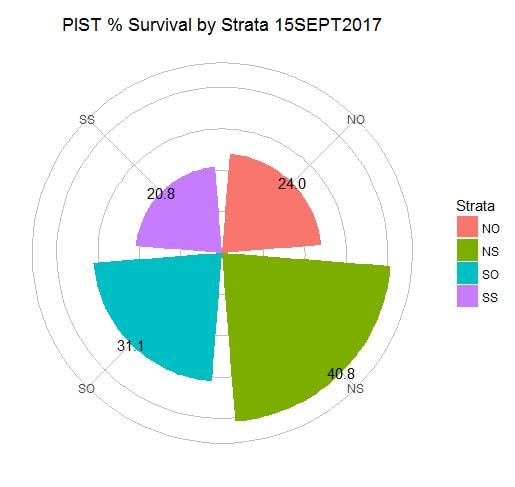

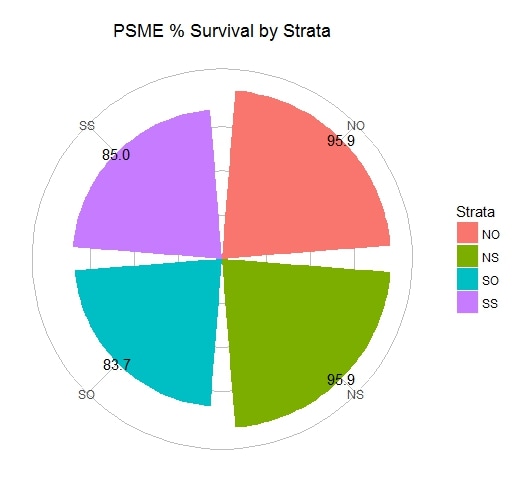

In a previous post about this project I recounted the trials and tribulations of elk eating our seedlings. Fortunately they didn’t get them all. We’ve been following these seedlings all summer to learn how survival varies as a function of aspect and vegetation cover. As a refresher on a previous post, we hypothesized that seedlings would be more likely to survive on north facing slopes and under the cover of shrubs, rather than out in the open on south facing slopes. The reason being that south facing slopes without shrub cover would be hot, dry, and stressful for seedlings. What are we finding so far… Well, it depends. Douglas-fir is what we call a more shade-tolerant species, meaning it can tolerate lower light environments when it is a seedling. As of 15 September, this species had the highest survival on north facing slopes and under the cover of shrubs. Ponderosa pine tends to be more shade intolerant, meaning it prefers a higher light environment. In this case we found that south aspects, regardless of shrub cover and north aspects with shrub cover all had 64-66% survival. North aspects without shrub cover had 76% survival. This suggests that they are getting the light they need, but are benefiting from it being a little cooler and moister on the north facing aspects without shrub cover. Pinyon pine, which is a species that grows at lower elevations and tends to regenerate in the shade of adult trees and shrubs is a bit of a mystery right now. It had higher survival on south facing slopes without shrubs and on north facing slopes with shrubs. We’re going to have to keep following this species and dig into the temperature and relative humidity data to figure out what is going on. Southwestern white pine is a species that tends to be intermediate in terms of shade tolerance, similar to Douglas-fir. This species also tends to occur at higher elevations in the Jemez with Douglas-fir because it requires more precipitation. These seedlings did best on north facing slopes, growing under shrub cover. Interestingly, it did better on south slopes in the open than it did on north slopes in the open. This result is another head-scratcher that is going to require digging into the data. We are nearing the end of the first growing season for these seedlings that we planted last fall. We’ll keep tracking these individuals to see how they do during the next growing season and we’ll be planting some new sites this fall. So, stay tuned for more results from our experiment trying to understand tree seedling establishment in a severely-burned landscape.

0 Comments

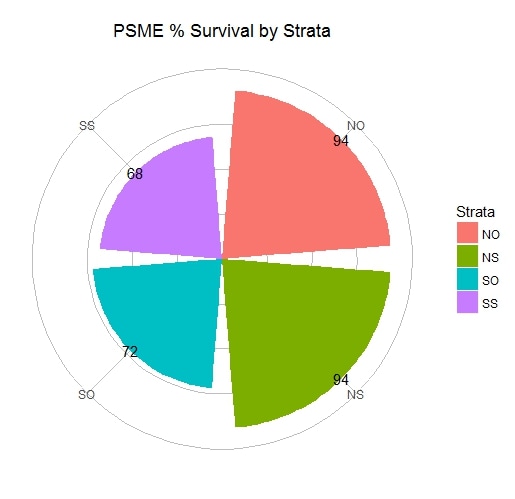

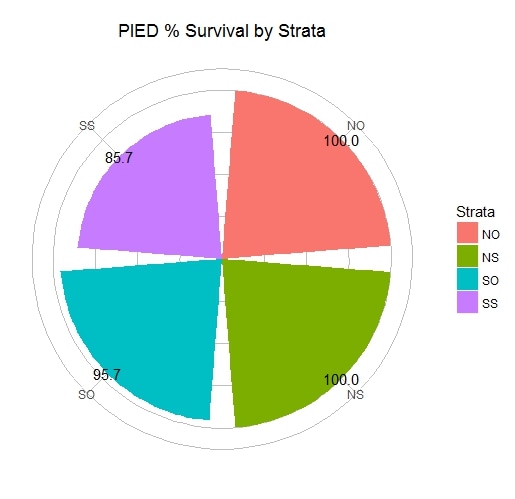

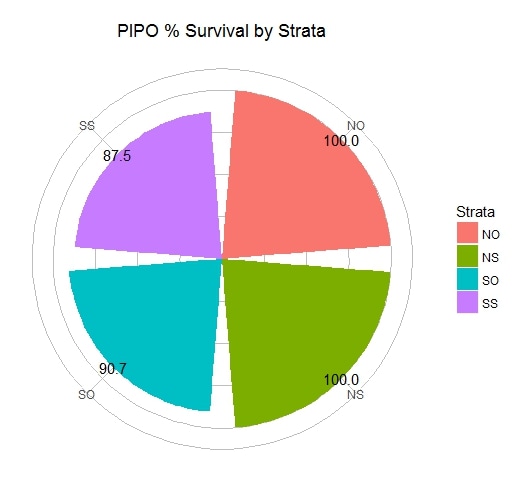

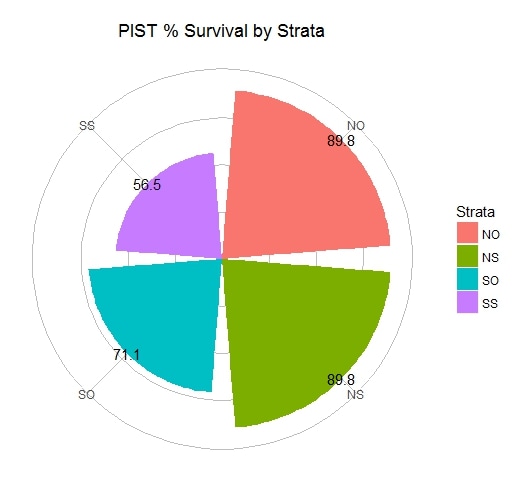

We were out on 18 April 2017 to conduct a post-snow melt, pre-dry season seedling survival survey on our plots in the Jemez Mountains. You can read more about the overall project here, but a quick recap: We planted seedlings from four species stratified based on aspect (north, south) and cover (shrub, no-shrub) this past fall in the footprint of the 2011 Las Conchas Fire. We found that our elk deterrent fencing was inadequate in a few areas and that mmmm, soil moisture and temperature sensor wires sure do look tasty to an elk. S.H. Hurlbert in his classic 1984 paper on pseudoreplication states that replication controls for, among other things, “non-demonic intrusion”. He then goes on to state “If you worked in areas inhabited by demons you would be in trouble regardless of the perfection of your experimental designs. If a demon chose to “do something” to each experimental unit in treatment A but to no experimental unit in treatment B, and if his/her/its visit went undetected, the results would be misleading.” Further in the same paragraph he states “Whether such non-malevolent entities are regarded as demons or whether on simply attributes the problem to the experimenter’s lack of foresight and inadequacy of procedural controls is a subjective matter.” I guess in the case of our planted seedlings, we foresaw the potential for elk to eat our seedlings and therefore exhibited some experimental foresight. However, we didn’t foresee the appeal of sensor cables to elk. Either way, it looks like we’ve got a case of “non-demonic intrusion” and a case of “demonic intrusion”. Fortunately, it is pretty clear when an elk decides to either eat the tasty seedling treat or just ripped it out of the ground and we can look at the effect of including this information or excluding it in a summary presentation of the information. Even though I still don’t have any resolution regarding whether or not elk qualify as demons, we can at least look at initial survival of the four different seedling species. The labels are as follows: PSME = Douglas-fir, PIPO = ponderosa pine, PIED = pinyon pine, and PIST = southwestern white pine. The strata are labeled as follows: NO = north aspect without shrubs, NS = north aspect with shrubs, SO = south aspect without shrubs, and SS = south aspect with shrubs. We had higher percent survival on north aspects for all species and lower percent survival on south aspects. Southwestern white pine (PIST) seemed to have an especially tough time on south aspects, as compared to the other species.

One of our hypotheses for this project is that seedlings will have higher survival on north aspects than on south aspects and that on south aspects, survival will be higher with shrubs than without. We’ll see how this plays out during the May-June dry period. So, stay tuned for the next post where we’ll also have some temperature and relative humidity data by strata as well. The 2011 Las Conchas fire burned 156,593 ac (63,370 ha) on the east flank of the Jemez Mountains in northern New Mexico. While certainly not the largest fire in recent years, this particular fire burned through three areas previously impacted by wildfire. This New York Times article provides a good overview of the issues facing this particular landscape and many western landscapes in general. In the southwestern US, the area burned by wildfire has increased 1266% over the 1973-1982 average. A recent estimate suggests that climate change contributed an additional 10.3 million ac (4.2 million ha) of forest fire over the period from 1984-2015, meaning that in the absence of climate change we would have expected about 50% less burned area over that period. As a result, severely burned landscapes like the east flank of the Jemez Mountains are becoming more common. Increasing fire size and larger patches of severe fire, where the majority of trees are killed, create a challenge for reforestation. The first challenge is distance to mature trees that provide the seed for tree establishment. This challenge can be overcome by planting seedlings. However, trees modify the climate conditions at ground level. Under the canopy of a forest, the air temperature is cooler and the relative humidity is higher, making it a moister environment. These factors matter because hot, dry conditions can be lethal to seedlings. In a burned patch where all of the overstory trees have been killed, these microclimatic conditions may be too harsh for seedlings to establish. We are in the process of establishing an experiment funded by the Joint Fire Science Program to figure out how the post-fire environment influences the ability of planted seedlings to survive and grow. The post-Las Conchas fire landscape has a mix of shrub and grass cover. Our hypothesis is that shrub cover could create more favorable growing conditions for tree seedlings. To test this hypothesis, we constructed exclosures in shrub and non-shrub patches and are in the process of planting seedlings. We are instrumenting these sites with sensors that measure temperature and relative humidity at the height of the seedlings. We’ll link the temperature and humidity data with data collected at weather stations that we are deploying around the experiment. This will allow us to model how microclimate (ground level temperature and relative humidity) vary across the larger area and predict how these factors influence tree seedling survival and growth. Stay tuned for updates on this project.

|

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed