|

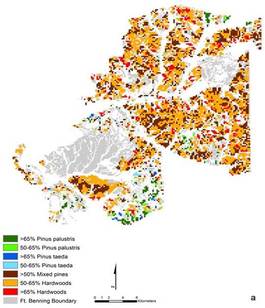

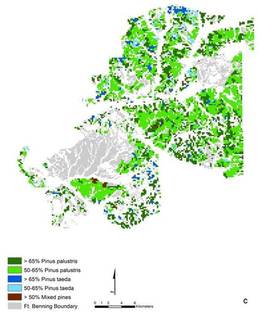

In our most recent paper, led by Katie Martin, we simulated the effects of different forest management actions on the provision of Red-cockaded Woodpecker (RCW) habitat and carbon sequestration and storage at Fort Benning, GA. The RCW is a federally protected species and Fort Benning is one of the core recovery sites in the recovery plan developed by the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The RCW preferentially nests in longleaf pine trees greater than 60 years old. Something that is in short supply in the southern pine belt since we converted much of the longleaf pine forests to plantation forests. At Fort Benning, they have been restoring longleaf pine forest to provide habitat for RCW and other species that are dependent on this forest type. Longleaf pine forest is a fire-dependent system, meaning that frequent fires in part maintain its structure and function. With funding from the Department of Defense's Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program we investigated how different forest conditions and management actions (restoring longleaf pine forest, prescribed burning, fire-exclusion) influence the development of RCW habitat and the resultant effects on carbon sequestration and storage. Using field data and the simulation model LANDIS-II we found that by actively restoring longleaf pine forest and regularly managing with fire, we can substantially increase the amount of forest that provides RCW habitat. However, this restoration comes at the cost of reduced carbon storage. Without regular fire, these pine forests transition to broadleaved forests (mostly oak species) and do not provide much RCW habitat, but do store more carbon. The map on the left shows the landscape after 100 years without active fire management or longleaf pine restoration. The map on the right shows the landscape with active longleaf pine restoration and regular prescribed burning. The areas of the maps that are green are the areas that provide forest habitat suitable for the RCW. Longleaf pine restoration and regular prescribed burning increase available habitat to approximately 92% of the landscape.

When we looked at the effect of these management options on carbon, we found that substantially increasing RCW habitat requires about a 22% reduction in carbon storage at the end of the 100-year period when compared to excluding fire from the landscape. We also need to consider how much carbon is being removed from the atmosphere each year by tree growth and how much is being emitted to the atmosphere from prescribed burning. We found that the balance of the carbon removed versus emitted was higher over the 100-year period when we actively restored longleaf pine forest. The importance of this finding is that while burning does return carbon stored in the forest to the atmosphere, regrowth by trees and plants quickly recaptures that carbon. In short, our findings demonstrate that providing RCW habitat does require a reduction in the amount of carbon stored in the forest. However, that reduction is not as large as we would expect given how frequently longleaf pine forests need to burn.

2 Comments

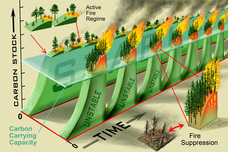

In scientific inquiry we start with a model (conceptual or otherwise) about how we think some aspect of the world works. We use that model to develop a hypothesis. We design an experiment to test the hypothesis and we either find support for it (fail to reject the hypothesis) or we don't (reject the hypothesis). One of the hypotheses that we have been testing in the lab is that when we restore dry, fire-prone forests by restoring fire as a natural process, the remaining carbon (trees are 50% carbon) is is less likely to burn up in a wildfire (i.e. more stable) than in an unrestored forest. The conceptual model that we are working with is that since we have been putting out natural fires in these dry forests for the better part of a century, the structure of the forest has changed (we now have more trees) and the amount of fuel (dead plant material on the forest floor) has increased. The change in structure and the build-up of fuel that make these forests more prone to wildfires that kill a large fraction of the trees has been demonstrated by many different studies in different locations. Agee and Skinner provide a review of the basic principles of these treatments in their 2005 paper.

When we restore forest structure by thinning trees and reduce fuel build-up through prescribed burning, carbon is removed from the forest (thinning) and emitted to the atmosphere (burning). A number of studies have documented this fact in Arizona, California, and Oregon. To test the hypothesis about carbon stability we have evaluated field data and measures of fire risk and we have run simulation model experiments in Arizona and California dry forests. We continue to get consistent results - thinning and burning reduce the amount of carbon stored in the forest and reduce the risk of high-severity fires that kill many of the trees - and have failed to reject the hypothesis. That does not mean that we have found a universal truth - it is likely that we would reject this hypothesis if we tested it in a wet forest (see Steve Mitchell's results from coastal Oregon forests for an example). I bring this up because I gave a presentation on this topic the other day. At the end of my talk I got a number of great questions. Some I could answer with certainty and some required the caveat that it is possible given what we know currently. The questions I couldn't or wouldn't answer were the ones that crossed the line I have personally set as the boundary between data-driven conclusion and opinion. These are typically questions that include some form of "What should we do?". In his book The Honest Broker, Roger Pielke, Jr writes extensively about the different roles that scientists can play in the policy discussion. Pielke argues that we should aim to be "honest brokers of policy alternatives", meaning that scientists should not seek to limit the range of available options. I teach a graduate course in which we read and discuss Pielke's book, among others, and evaluate the effects that taking any one of these roles can have on an individual scientist's credibility and the outcome of the decision-making process. After numerous readings and discussions, my understanding of the concept continues to evolve. Currently I evaluate whether or not I'll respond to a question by asking myself if my scientific understanding of the system or topic can provide a piece of information useful to the discussion. As an example, following my presentation I received one question regarding treatment prioritization in a time of limited budgets and whether we should prioritize treatment in undeveloped areas or in areas where forests and communities meet. Do I have an opinion on the topic? Sure. Does my standing as a scientist that studies carbon dynamics in fire-prone forests give my opinion more weight than a person who lives in a community with high fire risk? Absolutely not? There are many things that I enjoy about speaking to groups outside of the scientific community. I like the fact that it pushes me to reduce the field-specific jargon. I like the challenge of assembling my research for a non-specialist audience. I like the questions that push me to think about the science in a new way. But, my favorite part is that it pushes me to evaluate where the line between data-driven conclusions and opinion lies. Much the way that my conceptual model of the forests I work in evolves with more information, my perception of my role as a scientist communicating outside of the scientific community evolves with more experience. |

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed