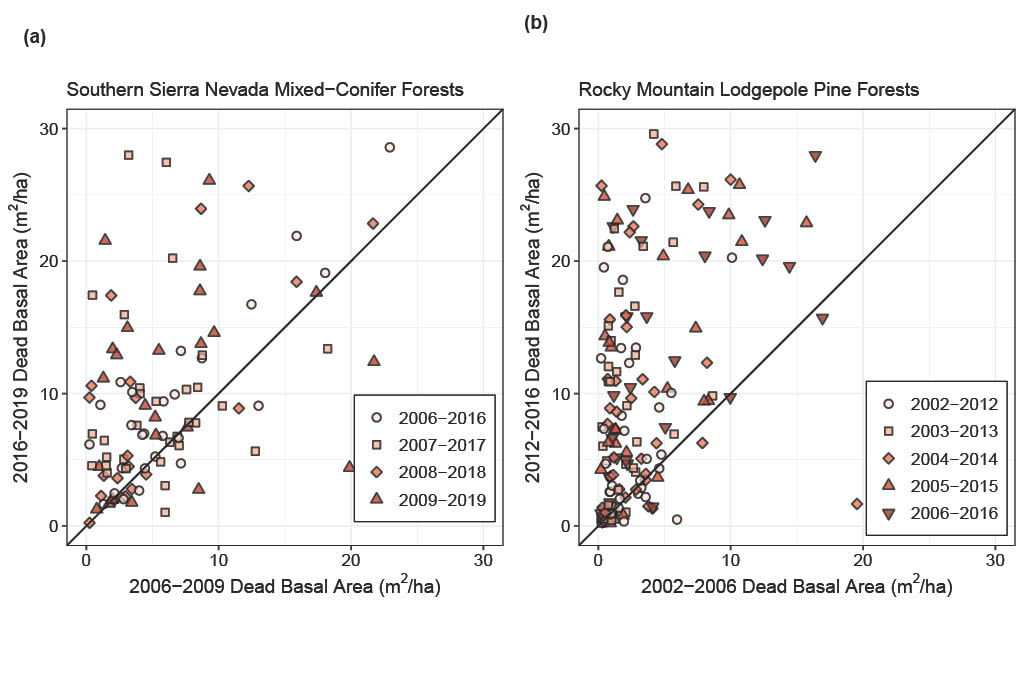

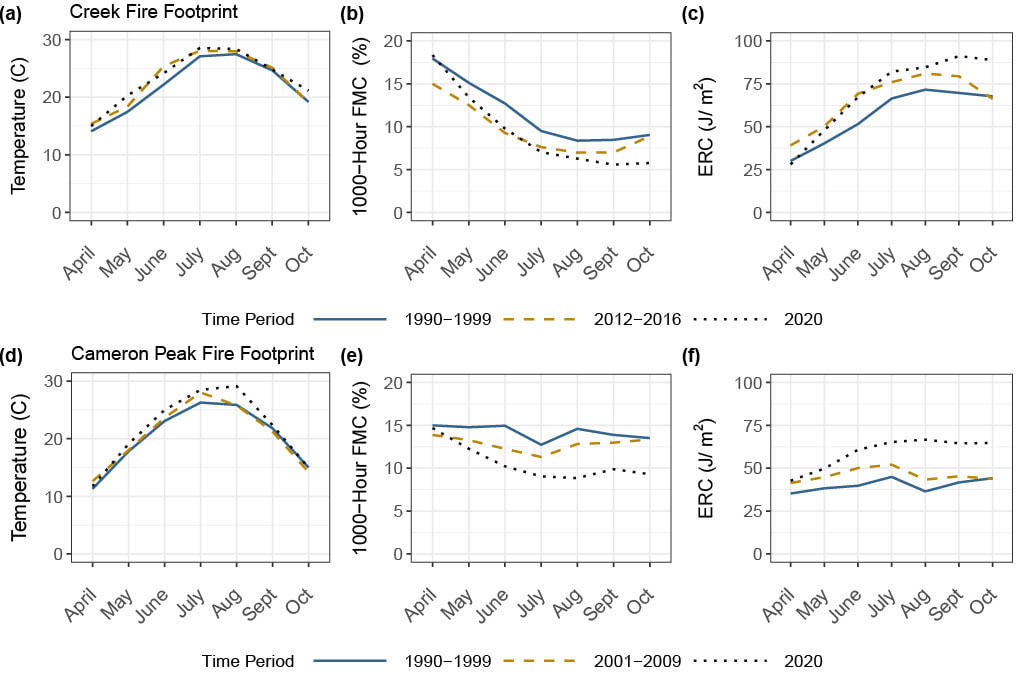

by Marissa GoodwinRising temperatures are drying out forests in the western US. As temperatures increase, so does the atmosphere’s demand for water, a relationship known as the vapor pressure deficit. Numerous studies have shown that as vapor pressure deficit increases with climate change, the amount of water stored in both live and dead vegetation decreases. In fire-prone forests, this means that the fuel loads in these systems are becoming drier making them more available to burn when wildfire occurs. This is because the amount of water stored in live and dead vegetation (known as fuel moisture content) controls the amount of time and energy needed to vaporize that fuel moisture before ignition can occur. As fuels dry out, they burn more readily, and as a result we have seen an exponential increase in the forest area burned in the western US. Climate change has increased drought frequency and severity as well as insect outbreaks which has resulted in widespread tree mortality. The substantial tree die-off from these mortality events increases the total amount of dead fuels available in the forest, which are inherently drier than live trees. Because fuel moisture content regulates the amount of heat energy that is released during wildfire, fires that occur where there is a surplus of dead fuels may release a significant amount of energy as heat. Consequently, the combined effect of rising temperatures and widespread tree die-off on fuel moisture content may in part be responsible for the unprecedented wildfire behavior we have seen in recent years. In our recent study, we assessed how the combined effects of tree mortality and rising temperatures increased fuel availability and potential heat energy release in the areas where two megafires occurred: the Creek Fire in the southern Sierra Nevada of California and the Cameron Peak fire in the Rocky Mountains of Colorado. Both fires occurred during the 2020 fire season and were preceded by widespread tree mortality. The Creek Fire was one of the largest in modern California history and burned in an area where the 2012-2016 drought and bark beetle outbreak resulted in widespread tree mortality. The Cameron Peak Fire, which was the largest in Colorado history, burned through forest with large numbers of bark beetle-killed trees. In our study, we used temperature and fuel moisture content data to calculate changes in fuel availability in these two forests over the past three decades. Additionally, we calculated how this influenced the amount of heat energy that could be released during these wildfires and how the transition of trees from live to dead fuels influenced potential energy release. We found that tree die-off in these two forests transitioned substantial amounts of biomass from live to dead fuel pools. This transition, coupled with reductions in fuel moisture content from rising temperatures, resulted in substantial increases in fuel availability and the amount energy available for release in the areas where these two fires occurred. For example, in the footprint of the Cameron Peak fire, we estimated that higher temperatures coupled with dead fuel loading from beetle mortality resulted in a 55% increase in fuel availability and a two-fold increase in potential energy release. Because heat energy release drives fuel ignition and wildfire spread, our results suggests that the combined effects of tree mortality and rising temperatures likely play a role in the unprecedented fire behavior that has characterized modern wildfires. Fires that occur where there is surplus of dry, dead fuels may be perpetuated not only by available fuels, but also by the substantial amounts of energy they release.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Details

Archives

October 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed